Long Li didn't ask what was in it. All she knew was that she was supposed to use it to clean cell phone screens, hundreds of them every hour. Fumes filled the air in the windowless room where she worked, in a three-story factory outside the southeastern China city of Dongguan.

Long, the 18-year-old daughter of peasant farmers from Guizhou, was supposed to dip her rubber-gloved right index finger into the oil and then rub each screen for 10 to 20 seconds. The company—Fangtai Huawei Electronic Technology—gave Long and her coworkers paper masks, but they rarely used them. They were too hot, and anyway the women who worked there often exhaled onto the screens because the condensed moisture from their breath made cleaning easier. Long worked from 8 am until 11 pm, and as late as 4 am in the busy season.

She didn't complain. Long had fallen onto a kerosene lamp when she was 1 year old and burned her face; her father told her she had to be extra cheerful to make up for the scarring. Long had hoped to be a teacher for blind and deaf children, to help them through their own disabilities, but, tired of watching her parents labor in the field day after day, Long left for the city in the winter of 2011. At Fangtai Huawei, with overtime she could earn as much as 3,000 yuan (about $485) a month to help her family.

Long moved to Dongguan when the working conditions of Chinese tech laborers had become an international issue. Suicides in 2010 at a factory owned by Foxconn Technology Group—a supplier for Apple, Hewlett-Packard, Sony, and other transnational companies—sparked investigations that found laborers were working long hours for insufficient pay and living in substandard housing. In response, in March 2012 Foxconn pledged to make things right. Apple and Samsung publicly investigated their Chinese supply chains and promised to hold contractors to Western health and safety standards.

But if working conditions were improving at Chinese factories, Long did not see it. Soon after she began working at Fangtai Huawei, her fingertips started tingling. After a few months, her feet and hands were numb. Long couldn't hold the screens properly. Her coworkers started getting sick too—Zi Renchun, a 25-year-old from Yunnan province, lost her appetite. Shang Jiaojiao, who had begun working at age 14, had joint pain and eventually could barely lift herself out of bed. By summer, some of the workers were collapsing.

I saw my son, but it was not my son. He was in a coma, his face was swollen, his eyes shut. It was like my soul escaped from my body.

In mid-July, Long found herself unable to move her legs. “I was just lying on my bed all day and needed help to eat,” she says. Long ended up in a hospital in Guangzhou with more than 30 other Fangtai Huawei workers. Doctors found they'd been exposed to n-hexane, presumably in the “banana oil.” It's an industrial solvent that causes neurological damage at just 50 parts per million. Workers using it are supposed to wear respirators and operate in a ventilated area. As treatment, Long endured daily injections—she says they “hurt more than anything else in the world.” We interviewed her in a hotel a few blocks from the hospital; officials there wouldn't answer our questions or allow us to see her on the premises. Long still tries to stay cheerful. “When I cry,” she says, “I cry secretly.”

Even after the reforms triggered by the Foxconn scandal, thousands of people like Long arrive young and healthy in China's cities every year only to face the health consequences of working for factories with inadequate labor safeguards. Nobody really knows how many are injured or get sick; official Chinese government statistics put the workplace injury rate at 115 per 10,000 workers—slightly higher than the US and significantly higher than the European Union. But few observers trust China's numbers. The government underreports occupational injuries, and one survey found that as many as seven out of 10 migrant workers, who make up a third of the workforce, don't participate in China's workers' compensation system.

Over the past two years we have interviewed multiple experts and 70 workers at 15 Chinese factories. Our investigation suggests that while some Chinese companies raised wages and reduced working hours, other problems with workplace health and safety remain unresolved. In many cases, companies have merely pushed the problems outward from their own factories to contractors and subcontractors, where compliance is more difficult to enforce. The underlying dynamic has not changed: Squeezed by global brands to produce ever-cheaper high tech products, Chinese factories continue to cut corners on safety.

But the problems don't end in the factories. Changes to China's workers' compensation system require companies to pay into a fund and then pay a portion of an injured worker's salary, living expenses, and medical care. So companies now have a motive to deny that workers were injured on the job. Government corruption and interference cause further delays and setbacks for patients, who are often left struggling to pay for treatment out of pocket for years or are trapped in lengthy legal fights. Many Chinese factories are still unsafe, and a tangled health care system prevents workers from getting help. Put simply, China's tech-factory workers are getting red-taped to death.

According to the China Labor Support Network, more than a quarter of the labor force in China is at risk of occupational poisoning.

Sim Chi Yin/VIIDuring the Foxconn scandal, analysts connected unsafe conditions to the demand for cheap devices in the West. “A huge issue is how companies walk the line between trying to get the best financial performance and also achieving high safety standards,” says Kate Cacciatore, former corporate responsibility director at STMicroelectronics. “There is a constant pressure on companies to cut costs, and that pressure works itself down the supply chain.”

Cacciatore is a former board member of the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition, a group of 105 electronics companies formed in 2004 in response to criticism of conditions at contract manufacturers. Their code of conduct requires that member companies monitor and control chemical exposure and other risks. But the EICC doesn't set specific numeric standards, instead deferring to local laws. That's quite a loophole. Member companies complete a self-assessment to identify the greatest areas of hazard and, to complete admission, the EICC assigns an auditor. The group has never expelled a member for failing to live up to its code. Also, EICC standards apply only to suppliers that represent 80 percent of a company's total spending. That's most likely the first tier of contractors in the supply chain—companies that make or assemble components for member companies—or the second- or third-tier suppliers, contractors to the contractors. Companies further down the line aren't monitored.

Even figuring out who those companies are turns out to be problematic. Four workers at Fangtai Huawei said they worked on products for Nokia, Samsung, and Chinese electronics giant TCL during their time at the factory. Long claims she worked on Apple products. Other workers said they physically delivered products to companies that supply Apple, Samsung, TCL, and Microsoft.

But did the company actually make products for those big-name clients? Fangtai Huawei representatives denied requests for an interview. The Chinese technology industry is rife with counterfeits and copyright violations; it's possible the workers at Fangtai Huawei saw logos on fakes. Interrelationships along the supply chain in China are byzantine.

In theory, workers compensation law protects Chinese employees, but in practice, abuses prevail.

Considering Apple's reputation for precise control of its supply chain, it's nearly impossible to imagine the company doesn't know who makes the screens for its flagship product. Chris Gaither, Apple's director of corporate public relations, says the company scoured its contractor database and found no mention of Fangtai Huawei. Apple also queried Foxconn, and the manufacturing giant denied having any business with Fangtai Huawei. Samsung representatives said the company has “no relationship” with the manufacturer. Microsoft acquired Nokia's cell phone division in 2014, but a spokesperson at Microsoft referred our questions to Nokia, and Nokia's spokesperson said the company had not been a supplier since 2004. TCL didn't respond to our request for comment. But Fangtai was making screens for someone.

Apple is particularly sensitive to claims of neglect. The company surpasses EICC standards and has an updated code of conduct and a 100-page list of work requirements for suppliers deep into the supply chain. The Apple Supplier Environment, Health, and Safety Academy, an 18-month program with over 150 hours of training, teaches managers proper risk management and safety standards. And the company performed 633 audits at facilities worldwide in 2014, nearly three times as many as in 2011.

Still, Apple's own reports show that 30 percent of its suppliers don't comply with the company's own safety standards and 18 percent fail to comply with standards on hazardous chemical exposure. In fact, the company finds some level of noncompliance in every annual report. But Apple says that's just evidence that the process works—that the company helps its suppliers resolve every violation. “People sometimes point to the discovery of problems as evidence that our process isn't working,” wrote Apple's senior vice president of operations, Jeff Williams, on the company's supplier responsibility website in February. “Nothing could be further from the truth.”

Other investigations have found serious issues with suppliers in China. China Labor Watch, a nonprofit with bases in New York, Sichuan, and Shenzhen, interviewed workers and sent undercover operatives into 14 Apple suppliers in China in 2012 and 2013. Despite Apple's commitment to provide at least 24 hours of safety training, CLW found workers had eight hours at most, and often less. In late 2013, CLW discovered that at least five workers had died at the Shanghai factory of Pegatron, a Taiwan-based supplier producing the iPhone 5c, though CLW couldn't link the deaths to working conditions. Pegatron eventually said it would investigate, though when we asked for the results the company declined to comment. Apple policy is to respond to all specific allegations, and in this case, after sending its own team to the factory, Apple said it found “no evidence of any link to working conditions.” Last summer, reports said that Pegatron would be a supplier of the iPhone 6, producing 30 percent of the phones, with Foxconn producing the rest, and that Pegatron would expand its workforce at one factory by a third to fill the orders.

In 2012, CLW investigated 11 Samsung factories, six of which were majority-owned by the company. While the group found labor violations at all of them, the problems were particularly egregious at some independent suppliers—no safety training, no masks for workers in contact with fumes. Samsung told us that “corrective measures have already been taken” but didn't offer specifics.

SICK DAYS

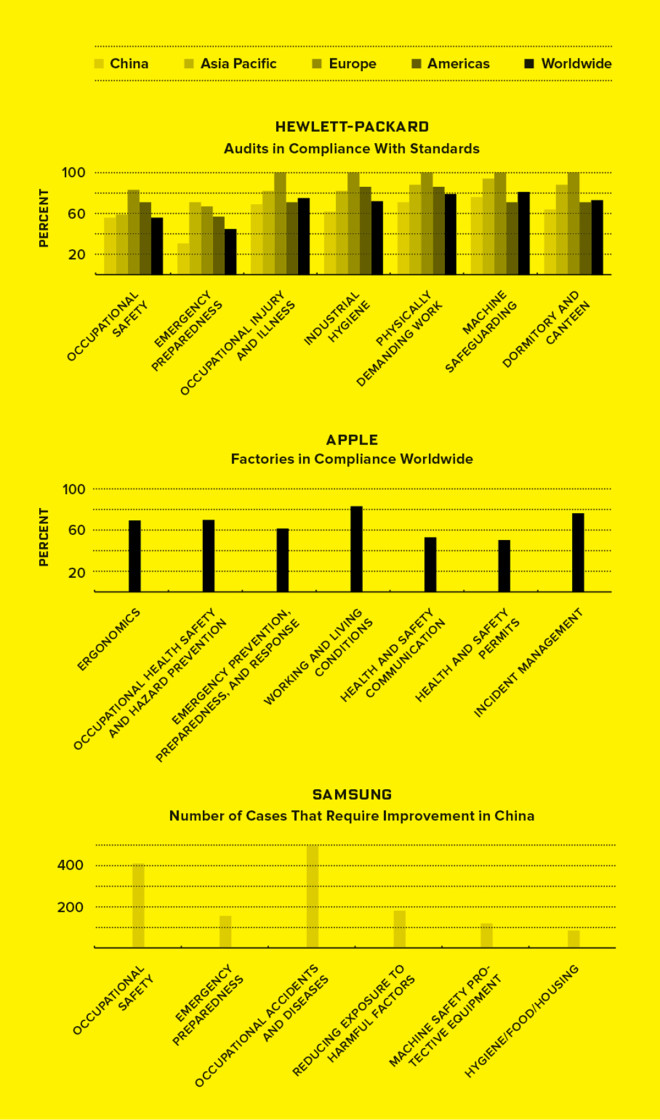

Maintaining humane working conditions requires codes that regulate everything from injury prevention measures to dorms and dining facilities. But when HP, Apple, and Samsung— the top three makers of information and communications hardware—conducted audits of their factories, they found plenty of room for improvement.—VICTORIA TANG

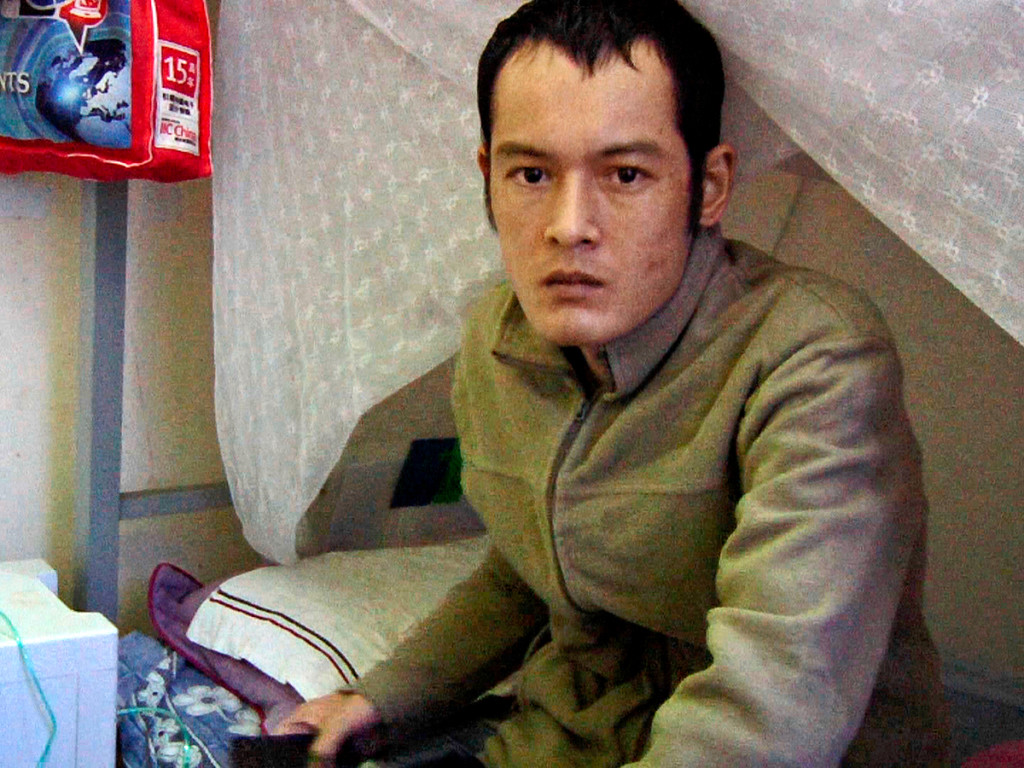

Ming Gaosheng leads the way down a trash-strewn alley in Shenzhen. Together we climb four flights of stairs to a tiny apartment, where Ming's son Kunpeng pokes his head out of his room. He's stick-thin, wearing red athletic shorts. Green tubes run from his nose to an oxygen tank. Removing them, he sits down on a wooden bed frame in the kitchen, every once in a while interrupting himself with a phlegmy cough. His story is about more than just working conditions. It's about health care for people who get sick or hurt on the job.

In 2007, when he was 20 years old, Ming Kunpeng began working at a factory then owned by Dutch company ASM International—a leading manufacturer of assembly equipment for computer chips, phones, and tablets. For two years, Ming cleaned motherboards with chemicals including benzene, a sweet-smelling and particularly effective industrial solvent and degreaser. It is also a carcinogen. Where people still use it, the International Labour Organization recommends wearing helmets with a face piece blowing clean air and gloves made of Viton, an expensive heat- and chemical-resistant fluoroelastomer. Ming Kunpeng says he was given only masks and standard gloves.

In 2009 he was diagnosed with leukemia from benzene exposure, according to medical records. But as recently as 2013, changes to China's health care system continued to make health care untenable for him—and many others with work-related problems. When the family asked ASM for compensation, the company refused to pay, disputing the cause. They fought for a year, while Ming waited for a bone marrow transplant. In desperation, his family says, they agreed to a onetime settlement in return for dropping their case. Ming got the transplant, but his lung collapsed a few months later, leading to an almost permanent need for an oxygen tank. In 2011 he was hospitalized full-time. The family moved from their village in Hubei province to be nearby. “We don't dare expect anything else from the factory,” his father says. “The company gave us a sum of money, and now our relation is no more.” (For its part, a spokesperson for ASM denied that the chemicals Ming was exposed to included benzene.)

Though the family had his medical bills reimbursed by the government, they had to pay some costs out of pocket. Ming Kunpeng had his own room, but his brother's family slept together in a large bed in another room, and his parents slept in the kitchen. “Back home, we have our own land. We eat what we plant. Here it is so expensive,” Ming's father says.

A few months after we interviewed the family, Ming Kunpeng climbed to the roof of the hospital where he was receiving treatment and jumped, killing himself. His family told us he felt he had become a burden.

Before 1994, the Chinese government owned most of the country's factories and covered almost every citizen's medical costs. But as China has moved from a socialist economy to a partially privatized one, the “iron rice bowl” that covered health care from cradle to grave has given way to private insurance. To protect workers, the state requires all industrial companies to pay about 1 percent of each worker's salary into the Industrial Injury Insurance Fund, with about $16.2 billion in assets. The local government administers payments. When workers get injured, the fund is supposed to pay medical expenses, living expenses, and survivor benefits. Employers, furthermore, are supposed to continue paying the employee's full salary and, depending on the type and severity of the injury, might also have to pay a portion of medical bills.

In theory the law protects workers, but in practice, abuses gut it. That's the conclusion of Zhai Yujuan, a professor of labor law and social security at Shenzhen University. Zhai has studied occupational injury and workers' compensation in China for a decade and has written several books on the topic. In her estimation the system needs reform. “In some cases the companies just pay the 1 percent, but they don't want to pay for additional compensation,” Zhai says. Worse than that, by some estimates fully 75 percent of companies fail to pay into the insurance system at all. Technically, a nonpaying company is supposed to pay the salary and expenses for an injured worker—a responsibility it often tries to avoid. “It's a loophole in the system,” she says.

The catch for workers trying to claim compensation is that, by law, they need two documents: confirmation they worked at the specific factory and a diagnosis from a federally certified medical clinic that shows the injury was work-related. Getting both documents is an onerous process, even after the government reformed the system in 2012 to allow workers to get them at the same time instead of sequentially. Companies often block one or both, Zhai says, either denying workers the proof of employment or putting pressure on the hospitals to issue a less severe diagnosis (or to deny the injury or illness was work-related at all). “If you get leukemia, they will say it's tuberculosis,” Zhai says.

1 / 3

Long Li collapsed, legs paralyzed. Courtesy of Heather White

2 / 3

Ming Kunpeng, who was given little protective equipment at his job, got leukemia. Courtesy of Heather White

3 / 3

Zhang Tingzhen fell at work and suffered a traumatic brain injury. Courtesy of Heather White

Workers from the countryside, whose villages might be hundreds of miles away, are required to stay in the city where they worked to continue to receive treatment from designated regional health clinics. Many opt to receive a onetime settlement from the company—frequently less than the cost of their medical bills—instead of fighting for the proper documentation and diagnoses, which can drag on interminably. “It can be like one or two years or up to 10 years. And because the process is so long, in the meantime you have to pay out of your own pocket,” Zhai says. Many leave. “They want to just get their big package of money and go home.”

Entire wards of Shenzhen hospitals are filled with patients injured on the job. Traumatic injuries are common—hands lost to factory machinery, for example—and victims face the same obstacles as people with chemical exposure. In one of the largest hospitals, People's Hospital Number 2, we meet a former equipment maintenance engineer named Zhang Tingzhen, an honors student and a champion athlete in his province, who in October 2011 fell while working at Foxconn's Shenzhen factory and suffered a brain injury.

When his father, Zhang Guangde, found out, he took the next train to Shenzhen. By the time he arrived, his son had already undergone two operations, one of which involved removing the left side of his brain. “I saw my son, but it was not my son,” Zhang says, talking to us in an apartment next door to the hospital that he and his wife share with six other families. “He was in a coma, and his face was swollen, and his eyes were shut. It was like my soul escaped from my body.”

After lunch, Zhang takes us across the yard to the hospital to visit Tingzhen. Dressed in a pair of striped pajamas, the young man sits on the side of the bed, smiling pleasantly and speaking in simple words and phrases; he has the mental capacity of a 3-year-old, and he only somewhat remembers his parents and sister.

When Zhang tried to get compensation for his son in 2012, Foxconn would not provide documentation that he worked at the factory. Instead, the company claimed he was hired in Shenzhen for a position in another factory, in the city of Huizhou, 60 miles away, where wages were lower and where Foxconn would be required to pay less compensation. The company refused to pay unless Zhang left Shenzhen and submitted to a government medical assessment in Huizhou. His father says his son is not able to travel.

Factory uniforms and young people’s clothing hang on laundry racks in an apartment block rented out to migrant workers.

Sim Chi Yin/VIIThat left the family in legal limbo—without occupational injury documentation, the government wouldn't pay. So Zhang Guangde started protesting—an extreme step in China, where labor activists are routinely harassed and jailed. Eventually Foxconn agreed to provide 11,000 yuan (about $1,800) a month. “The company has been very responsible in meeting and continuing to meet its obligations to Mr. Zhang,” Foxconn said in a statement, “including the provision of financial, medical, and rehabilitation care.” But Zhang says it wasn't enough, that the family has gone 30,000 yuan in debt paying for medicine and expenses, and that Foxconn's payments stopped after just five months.

After leaving the hospital, we drive a half hour north to Foxconn's enormous campus, employing over a half-million workers. The main gate is like a border crossing, with trucks lined up at tollbooths seeking entry and another line full of product waiting to depart. Thousands of people in polo shirts color-coded to the division where they work—black, red, white—stream through the pedestrian gates. In 2010 this factory produced a reported 137,000 iPhones a day. Today that number is likely much higher. We arrive at dinnertime; the smell of roasting meat rises from dozens of stalls outside the gate amid a bazaar of cheap electronics and clothing, catering to workers as they get off their shift.

Zhang finds a spot on an overpass to unfurl a large banner decrying Foxconn as “the empire of inhumane thugs.” Curious workers gather to watch. “My son used to be an engineer, now he cannot recognize a single Chinese character,” Zhang shouts. “This is the company you are working for. My son is now a vegetable in the hospital and cannot recognize anybody.” He seems small, dwarfed by the giant factory rising behind him. Still, a crowd of 50 or 60 people gathers, most of them workers from the factory itself. Some take pictures with their iPhones.

After Zhang's protests, Foxconn resumed payments, but he believes that the company wouldn't be paying him anything at all if he didn't keep it up—and he still hasn't been paid the full amount of his son's salary and monthly care costs. As we watch, one passing worker shouts back at him, “Foxconn creates jobs!”

“Yeah,” Zhang answers. “But they also kill people.”

Zhang eventually sued Foxconn, but in 2014 a court ruled that his son did indeed have to get assessed in Huizhou to receive compensation—and Foxconn offered Zhang a onetime settlement of 2 million yuan if he would agree to say that his son worked in Huizhou and to recant his criticisms of the company. Zhang declined.

IN MAY 2014, Samsung issued a rare public apology. In its plants in South Korea, the company acknowledged, 26 workers got leukemia and lymphoma after working with undisclosed chemicals, and 10 died.

Many major electronics companies use benzene, and even the ones that forbid it don't seem to be enforcing that rule with their suppliers. The same goes for n-hexane. In 2010, Nokia issued a public statement saying that “n-hexane is not used in the manufacturing process of our products or their components.”

Two weeks after we sent Apple a list of questions that included inquiries about benzene and n-hexane, the company issued a statement specifically banning these two chemicals. (Gaither, the spokesperson, said that the company had been working on the issue for months.) “Apple treats any allegations of unsafe working conditions extremely seriously,” the press release said, pointing to its own investigations of 22 suppliers from March through June 2014. Four had been using benzene or n-hexane “in low concentrations,” with no adverse effects on workers, Apple said. Since then, the company said, it has updated its “tight restrictions on benzene and n-hexane to explicitly prohibit their use”—but only “in final assembly processes,” meaning once again that smaller subcontractors would not be bound by the policy. Moreover, many of Apple's final assembly facilities didn't use those chemicals anyway.

The Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition's code of conduct doesn't ban any particular chemicals, though the organization is considering it. Fundamentally, companies use these toxic chemicals because of cost. Safer alternatives exist, but they're more expensive, as are proper ventilation systems and training. “If someone is on a 12-hour shift, you'd need three sets of gloves. In factories with 40,000 or 50,000 workers, that would be very expensive,” says Garrett Brown, a former compliance officer with the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health who has been investigating factories in China for more than a decade. “It makes much more sense to substitute a less-toxic chemical or use it in a way where there is near-zero exposure.”

Watch a trailer for coauthor Heather White’s documentary, Who Pays the Price? The Human Cost of Electronics.

Whoever Fangtai Huawei builds components for, the factory has obviously fallen through a gap. The general manager of Fangtai Huawei refused to talk to us, but he told the Dongguan Times newspaper that the leukemia cases were “unexpected” since the company trained new employees on safety precautions. “We will try all means to save the workers and pay each of them a monthly salary of 2,300 yuan,” he said, adding that the factory would fully comply with government requirements. But the workers who got sick say no one told them the chemicals they were using were hazardous nor encouraged them to use even the meager safety equipment provided.

When they did get sick, they say, the company told several of them that the illnesses they were suffering from were an unrelated syndrome that had nothing to do with the working conditions at the factory. It was only when a critical mass of workers became ill that Fangtai Huawei took responsibility. The workers say the company provided them only with 2,300 yuan (about $370) a month, though most made more than that with overtime.

In the summer of 2013, after a year in the hospital, the workers got word that the company wanted them to sign a document stating that their rehabilitation was complete. “We almost died in that factory, and now they are telling us to leave,” Long Li says. Payments stopped arriving on time, and several of the workers staged a protest at the local labor bureau. Police arrested three of them, including Long. She spent the night in jail and while there texted: “I'm so scared. I want to kill myself.”

In February, Long finally went home to her family. The company continues to operate. Outside the factory in Dongguan is a deserted security booth with a paper in the window advertising jobs. “Only girls 18–35,” it reads. “Obedient to management. Able to take hardship.”

The Afflicted

Sim Chi Yin/VII

Sim Chi Yin/VIIXIE FENGPING, 36. After working for five years at Huasheng Electric Motor, Xie was diagnosed with leukemia in late 2013. Her responsibilities at the workshop put her in direct contact with hazardous printing materials. A doctor linked the cancer to benzene exposure, which Huasheng disputed. But the Guangdong Prevention and Treatment Center for Occupational Diseases analyzed an ink sample from the company and found xylene, methylbenzene, and ethylbenzene. The company paid for her first stage of chemotherapy and a bone marrow transplant (donated by her sister). Unable to afford the rest of the treatment on her own, Xie borrowed money from friends. She says Huasheng paid 1,300 yuan (about $210) a month for medical costs until last December, but now she's fighting for a 40,000 yuan (about $6,500) reimbursement.

Sim Chi Yin/VII

Sim Chi Yin/VIILIN SUBI, 30 In a factory manufacturing imitation iPhones, Lin used n-hexane as a cleaner. A few months in, she had a pins-and-needles sensation in her limbs. A hospital diagnosed her with nerve damage and estimated that the treatment she needed would take about two years, with an average monthly medical cost of 8,000 yuan (about $1,300). The factory paid only part of her medical expenses and has not contributed to her cost of living or loss of working time. When she started her job, Lin didn't realize she was pregnant with her second child. After her doctor warned her of the possibility of deformities, Lin decided to get an abortion. “At that moment, all I thought was I wanted to end my life. I couldn't even, however, lift a finger to kill myself,” she says.

Sim Chi Yin/VII

Sim Chi Yin/VIIHE, 20 He is recovering from organic-solvent poisoning. As a circuit board inspector in a small Shenzhen factory, she checked cell phone parts cleaned with an unknown chemical. “It smelled bad,” He recalls. “We just called it ‘circuit wash.’” The factory didn't require gloves. After about a month, she went to the hospital in September 2014 with a fever and rash. The Guangdong Prevention and Treatment Center for Occupational Diseases attributed her symptoms to working conditions. “I didn't know there were occupation-related diseases until I got sick,” He says. The factory paid only for her medical expenses at the center, not for prior costs. Fearing retaliation, He asked to be identified only by her last name.

Sim Chi Yin/VII

Sim Chi Yin/VIIYAO, 38 Leaving her son in the care of her parents in Hubei, Yao moved to Shenzhen to work in a camera factory. Her duties mostly consisted of cleaning glass optics, painting a coating onto parts, and polishing lenses. They exposed her to chemicals for up to 10 hours a day. A series of air-quality tests of her work environment revealed the presence of trichloroethylene, n-hexane, benzene, methylbenzene, and xylene. In 2007 she began experiencing constant headaches. Following her doctor's advice, she stopped working in July 2013. Yao requested to be identified only by her last name.